Ang Lee’s Whole Shebang

Ang Lee’s “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk” is the first feature film ever to be shot at 120 frames per second, overtaking second-placed The Hobbit (48 fps), which had doubled the industry standard 24 fps. Lee describes the combo of 3D, 4K HD and 120 fps as “The Whole Shebang”.

China has embraced the film, a China-US-UK coproduction, more than any other market, bringing the greatest box office returns, partly due to Lee’s popularity and partly because of a widespread penchant for new technology. Two of the six theatres worldwide capable of projecting the film in all its glory were in China. Hollywood executives and US audiences meanwhile, were largely unmoved.

Critical reaction to the 120 fps has been mixed. Some have called it “too real” or a distraction. Others have pointed out that the ‘hyper-realism’ it creates exposes the artifice of the performance. Variety’s Brent Lang delivered a balanced critique, concluding, “[the film] represents both a massive step forward for moviemaking and a painful reminder that innovation comes at a price. It is a beautiful mess.”

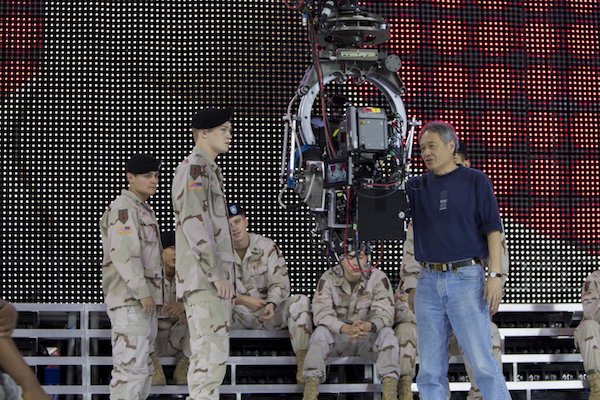

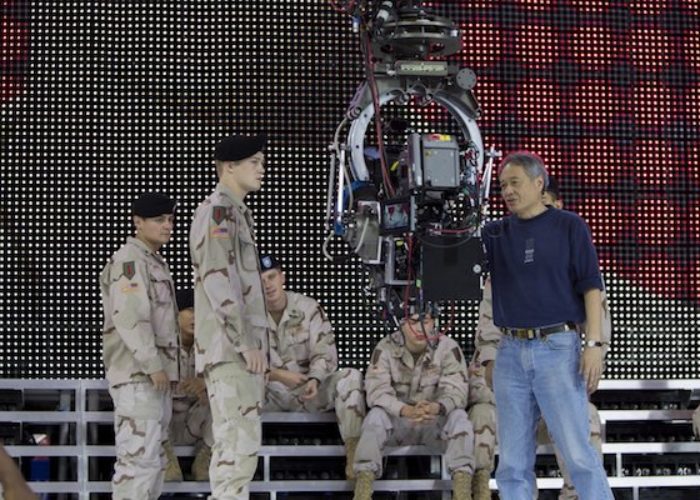

At the ICEVE conference at the Beijing Film Academy this month, the movie’s 3D Stereographer & Stereo Supervisor, Demetri Portelli proclaimed on stage, “I want to document this film in history as an important event.” We caught up with him to find out why.

120 fps “the ultimate solution”

When Ang Lee was looking for an “independent spirit” to help him realise his ambitious new project for under $50m with just 49 days shoot, he came looking for Portelli and digital engineer partner, Ben Gervais. Following $150m-plus budget 3D projects with Martin Scorsese’s Hugo, and 47 Ronin, the duo had confounded critics by proving that 3D could be efficient and affordable, delivering the 3D and VFX for Jean Paul Jeunet’s The Young and Prodigious T.S Spivet for under $2m in an overall project that cost less than $30m.

Demetri Portelli, 3D Stereographer & Stereo Supervisor of Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk at the ICEVE conference, Beijing

Demetri Portelli, 3D Stereographer & Stereo Supervisor of Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk at the ICEVE conference, Beijing

After Life of Pi, Lee was looking for a crisper image. Working at 24fps, he encountered a problem with motion and strobing when editing close-ups. “It was an ability to ‘lock in’ your eyes and look at somebody”, says Portelli. “He wanted to go to a high frame rate so that when you look at the face, you can lock in and hold your gaze on an actor’s eyes and stay there. That’s really important in communicating with the audience and having a true experience.”

Life of Pi, directed by Ang Lee, 2012

Life of Pi, directed by Ang Lee, 2012

Lee also wanted to separate himself from the classic film aesthetic. “Ang said, “I think you guys were all wrong on Hugo. You got the Alexa and tried to make a digital film look like an old movie. What’s wrong with taking a digital camera and trying to find new aesthetics that are intrinsic to digital cinema? We need artists to explore.”

The initial thinking was to shoot at differing frame rates – 24, 48, 60, 120 – which would have required commitment to decisions in principal photography. Shooting everything at 120 would mean capturing substantially more data – around 7.5 to 10 terabytes a day, roughly 40 times that of a normal 2D film – but would provide high quality images for every shot and ultimate flexibility in post.

In Lee’s office, in a custom-built postproduction unit cooled with powerful air conditioning, Lee exercised that freedom, adjusting the frame rate, depth and resolution to complement and enhance the action. “There are shots at 24 and 60 where he drops the aesthetic down to 2K to give it the old movie feeling,” says Portelli. “You can ramp scenes from 18 fps to 30 to 48. Maybe you’re in 2D but then you get into a close-up, and you go to 3D-120.”

The big close up shows the 120fps-4K technology best. The human face gives all the information

Ultimately, Portelli believes shooting at 120 fps makes every shot better, even if the frame rate is eventually dropped, “24 is better if you shoot 120 and deliver 24. The reason is you can control the shutter in postproduction. The hard thing for us in 3D was strobing and judder at 24. 120 is so smooth because you have all those frames, so nothing hurts.”

He continues, “By gathering more information, you’re delivering a better movie for everybody all the way down the line, including 2D, 3D, 24, 60, because you’re controlling the sequence of the frames, and you’re controlling clarity vs. blur. You’re controlling a cinematic look vs. a hyper real look.” That flexibility ultimately enables delivery in various different formats to suit any screen.

On set, Lee and Portelli would qualify each shot using a one-to-five “gear system” shorthand. For what Lee saw as “fantasy” characters like Billy’s love interest, they would go to 2D, a “low gear”. The fifth gear was reserved for the big half-time show and climactic battle scene. “For Ang”, says Portelli, “the whole shebang meant realism.”

Early on, the team had thought 120 fps shooting would best lend itself to action scenes due to its strength in capturing motion, but the real revelation was in the close-ups. “The beauty of 120 is that it shows everything, and it shows more. You start to understand the beauty that’s there in a simple close-up. It shows muscles, it sees through the skin. You can count the hairs in eyebrows and see the little expressions in someone’s eyes.”

“But,” he warns, “You have to be careful. It’s a very powerful tool. You can make somebody look very interesting but you can also make someone look a little bit ugly.”

He continues, “It reveals the artifice of filmmaking. The performance and the direction has to change, because if you see the actor thinking about his lines and looking down at his marks, he gives himself away.”

Portelli says naturalistic subjects are best. “We’re trying to show the world in a different light. Ang wanted to be bold, a project that put us in a natural environment in Morocco… and have you look at those little details in the sand and the dust.”

“People call it hyperrealism, but Billy Lynn is really just closer to just being a realistic project. I think 120 shows the world much closer to how we see it in daily life.”

Portelli calls Billy Lynn “the brightest film you’ve ever seen.” The initial idea was to project at a standard brightness of 14 foot-lamberts, “But before we had calibrated [the projectors], Ang looked at full brightness (28 foot-lamberts) and said, “My god, that’s amazing! He was trying to make a bold statement. We’re trying to give you an experience.”

Portelli describes it as a “sensory overload.” In fact, he says, “There are people who have gone to the film who have had a bit of anxiety because they’re not used to being put in that position as the viewer.”

There is room for improvement in the next 120 fps outing. The first challenge is to create smaller cameras than the hulking F65. In terms of postproduction, Portelli says, “I think we can do more variations and soften the DI a bit and be a little less heavy handed.” And of course, for more people to enjoy the experience, many more theatres will need to be capable of screening the full frame rate.

Lee’s next film, ‘Thrilla in Manila’ will be shot at 120 fps. “Ang does not want to work at lower than 120fps”, says Portelli. Lee hopes this will be the beginning of a movement. Whereas James Cameron has called 120fps a storytelling tool, Lee is calling it a format. “It’s not just a tool, this is a new way to see, so let’s start looking and let’s start talking about that. [Ang] is just beginning to discover a lot of new things. You will see a lot of change in his next film. Billy Lynn is just the beginning of what can you do with this.”