Stephen Chow & Hong Kong Mo Lei Tau Comedy

During the 1990s, Stephen Chow’s name became synonymous with a unique comedy genre known as mo lei tau. Though his recent movies retain many of the elements of his earlier work, the director is consciously moving away from the genre that made his name.

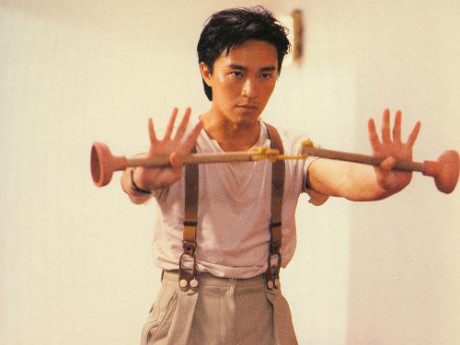

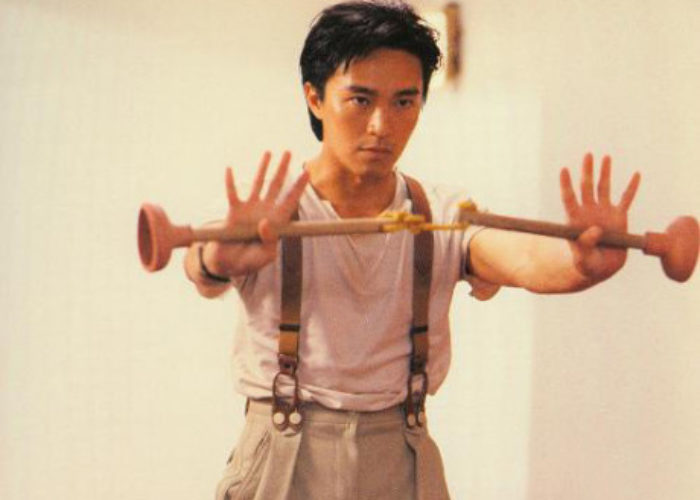

Stephen Chow

Stephen Chow is one of Hong Kong and China’s best loved comic actors and directors. His new film, The Mermaid, has broken all major China box office records including biggest opening day, single day gross and opening week of all time, ultimately becoming the highest-grossing film ever in China and the first to join the ‘3-billion-yuan club’. Whilst the success can be partly attributed to both the growing number of cinema screens across the country and the movie’s timely release to span two major holidays, the crucial catalyst is Chow’s enduring popularity.

Chow started out as a television comic actor in the late 1980s before getting his break in the 1990 movie All for the Winner. The subsequent wave of movies in which he starred, and sometimes wrote and directed, would become known as mo lei tau comedies and came to define the proceeding decade in Hong Kong moviemaking. The popularity of these movies saw Chow become Hong Kong’s leading comic actor and, alongside Chow Yun-fat and Jackie Chan, the major box office draw of the period.

Mo Lei Tau

Mo lei tau comes from the Cantonese phrase mo lei tau gau, which literally means ‘cannot differentiate between head and tail’, but is more commonly translated as ‘coming from nowhere’ or, more simply, ‘makes no sense’. The term describes a wave of lowbrow, anarchic and absurd movies that satirized society, flagrantly disregarding filmmaking and narrative rules such as the fourth wall. Whilst slapstick humour is central to the genre, it is perhaps most notable for its wild wordplay and creative license with the Cantonese language.

Video Clip from A Chinese Odyssey Part Two – Cinderella (1995)

Video Clip from King of Comedy (1999)

Though the term ‘mo lei tau’ wasn’t coined until Chow’s emergence, linguistic elements can be traced back to the Hui Brothers, a prolific Hong Kong moviemaking trio in the late 1970s. Jackie Chan’s slapstick Kung Fu roles in the 1980s continued the evolution, before Chow became the figurehead for mo lei tau films in the 1990s.

The reasons the genre emerged, flourished and became intrinsic to Hong Kong popular culture are tied to the sociopolitical climate of the time. The previous century had been a period of upheaval and transformation as Hong Kong grew from scattered fishing villages into a densely populated commercial hub, fuelled by an influx of migrants fleeing the political and economic difficulties on the mainland. By the early 70s, Hong Kong’s formerly immigrant population was beginning to seek and embrace its own, native cultural identity. A key element of that identity was language. In a nation where the youth spoke Cantonese but were made to learn and write in English and Mandarin, Chow’s wild abandon with linguistic conventions provided them with a new vernacular, that excluded non-Cantonese speakers, and which they could call their own.

Mandarin & The Mermaid

Poster from The Mermaid

Whilst the Stephen Chow’s films have been edging stylistically away from mo lei tau since 2004’s Kung Fu Hustle, they have still relied heavily on the key elements of the genre. The most significant departure began with 2013’s Journey To The West: Conquering The Demons, which saw Chow understandably embrace Mandarin to include and appeal to the enormous mainland audience. The decision goes against one of the fundamental tenets of the genre as a tool of defiance and consolation, exclusive to Cantonese youth. In this sense, whilst The Mermaid is an accomplished addition to Chow’s body of work, it seems that he has, for now, left mo lei tau behind.